A Vanishing Value Premium?

Weston Wellington, Down to the Wire

Vice President, Dimensional Fund Advisors

Value stocks under-performed growth stocks by a material margin in the US last year. However, the magnitude and duration of the recent negative value premium are not unprecedented. This column reviews a previous period when challenging performance caused many to question the benefits of value investing. The subsequent results serve as a reminder about the importance of discipline.

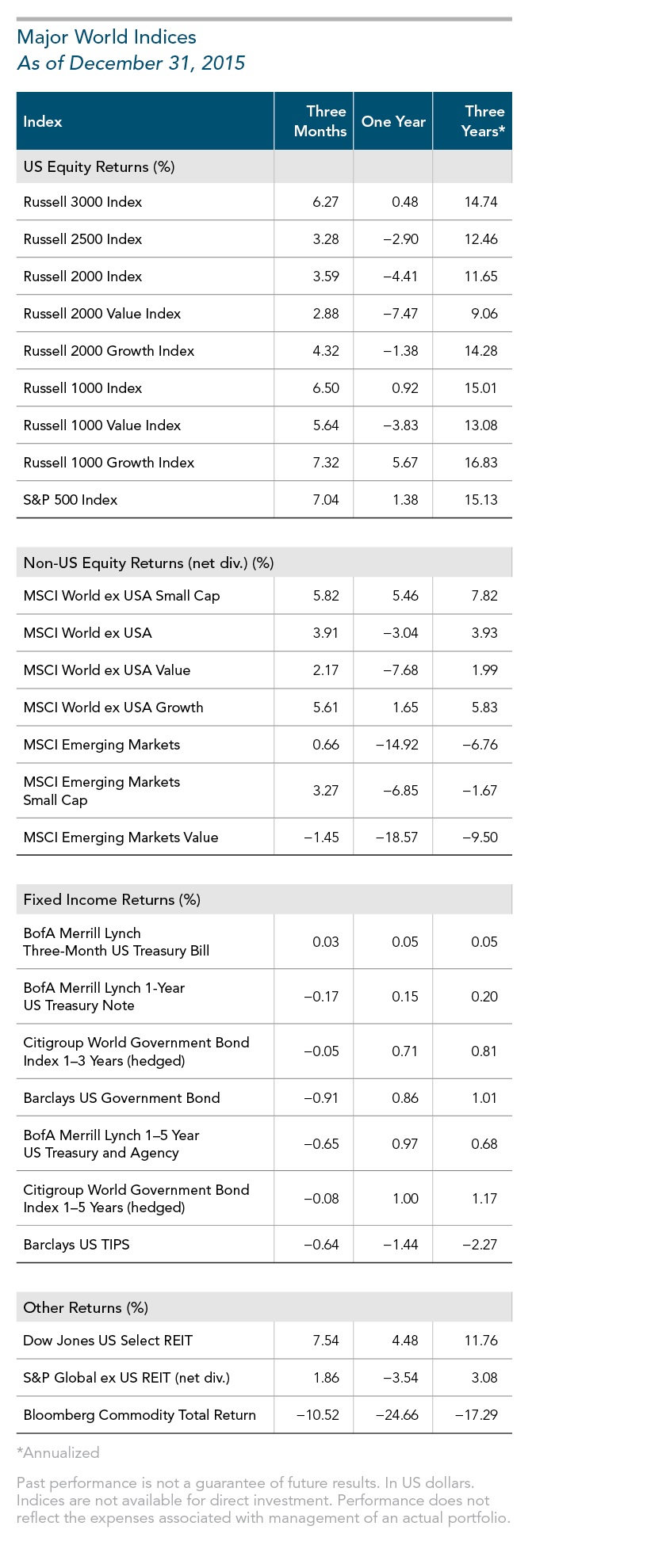

Measured by the difference between the Russell 1000 Growth and Russell 1000 Value indices, value stocks delivered the weakest relative performance in seven years. Moreover, as of year-end 2015, value stocks returned less than growth stocks over the past one, three, five, 10, and 13 years.

Unsurprisingly, some investors with a value tilt to their portfolios are finding their patience sorely tested. We suspect at least a few will find these results sufficiently discouraging and may contemplate abandoning value stocks entirely.

Total Return for 12 Months Ending December 31, 2015

Russell 1000 Growth Index 5.67%

Russell 1000 Value Index−3.83%

Value minus Growth−9.49%

Before taking such a big step, let’s review a previous period when value strategies under-performed to gain some perspective.

As many growth stocks and technology-related firms soared in value in the mid- to late 1990s, value strategies delivered positive returns but fell far behind in the relative performance race. At year-end 1998, value stocks had under-performed growth stocks over the previous one, three, five, 10, 15, and 20 years. The inception of the Russell indices was January 1979, so all the available data (20 years) from the most widely followed benchmarks indicated superior performance for growth stocks. To some investors, it seemed foolish for money managers to hold “old economy” stocks like Caterpillar (−3.1% total return for 1998) while “new economy” stocks like Yahoo! Inc. appeared to be the wave of the future (743% total return for 1998).

Many value-oriented managers counseled patience, but for them the worst was yet to come. In 1999, growth stocks shone even brighter as value trailed by the largest calendar year margin in the history of the Russell indices—over 25%.

Total Return for 1999

Russell 1000 Growth Index 33.16%

Russell 1000 Value Index 7.36%

Value minus Growth−25.80%

In the first quarter of 2000, growth stocks bolted out of the gate and streaked to a 7% return while value stocks returned only 0.48%. As of March 31, 2000, value stocks had under-performed growth stocks by 5.61% per year for the previous 10 years and by 1.49% per year since the inception of the Russell indices in 1979. A Wall Street Journal article appearing in January profiled a prominent value-oriented fund manager who regularly received angry letters and email messages; his fund shareholders ridiculed him for avoiding technology-related investments. Two months later he was replaced as portfolio manager amidst persistent shareholder redemptions.

With value stocks falling so far behind in the relative performance race, it seemed plausible that value stocks would need a lifetime to catch up, if they ever could.

It took less than a year.

By November 2000, value stocks had delivered modestly higher returns than growth stocks since index inception (21 years, 11 months). By month-end February 2001, value stocks had outperformed growth over the previous one, three, five, 10, and 20 years and since-inception periods.

The reversal was dramatic. Over the period April 2000 to November, value stocks outperformed growth stocks by 26.7% and by 39.7% from April 2000 to February 2001.

This type of result is not confined to the technology boom-and-bust experience of the late 1990s. Although less pronounced, a similar reversal took place following a lengthy period of value stock under-performance ending in December 1991.

We can find similar evidence with other premiums:

• From January 1995 to December 1999, the annualized size premium was negative by approximately 963 basis points (bps), amounting to a cumulative total return difference of approximately 113%. Within the next 18 months, the entire cumulative difference had been made up.

• From January 1995 to December 2001, the annualized size premium was positive by approximately 157 bps.

The moral of the story?

Prices are difficult to predict at either the individual security level or the asset class level, and dramatic changes in relative performance can take place in a short period of time.

While there is a sound economic rationale and empirical evidence to support our expectation that value stocks will outperform growth stocks and small caps will outperform large caps over longer periods, we know that value and small caps can under-perform over any given period. Results from previous periods reinforce the importance of discipline in pursuing these premiums.

References

Pui-Wing Tam, “A Fund Manager Sticks to His Values, Loses Customers,” Wall Street Journal, January 3, 2000.

Paul J. Lim, “Oakmark Ousts Manager Sanborn,” New York Times, March 22, 2000.

Standard & Poor’s Stock Guide, January 1999.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. A basis point (BP) is one hundredth of a percentage point (0.01%).

There is no guarantee investing strategies will be successful. Investment risks include loss of principal and fluctuating value. Small cap securities are subject to greater volatility than those in other asset categories.