By Jim Parker, Outside the Flags

VP, Dimensional Fund Advisors

Have you ever made yourself suffer through a bad movie because, having paid for the ticket, you felt you had to get your money’s worth? Some people treat investment the same way.

Behavioral economists have a name for this tendency of people and organizations to stick with a losing strategy purely on the basis that they have put so much time and money into it already. It’s called the “sunk cost fallacy.”

Let’s say a couple buy a property next to a freeway, believing that planting trees and double-glazing will block out the noise. Thousands of dollars later the place is still unlivable, but they won’t sell because “that would be a waste of money”.

This is an example of a sunk cost. Despite the strong likelihood that you’ll never get your money back, regardless of outcomes, you are reluctant to cut your losses and sell because that would involve an admission of defeat.

It works like this in the equity market too. People will often speculate on a particular stock on the basis of newspaper articles about prospects for the company or industry. When those forecasts don’t come to pass, they hold on regardless.

It might be a mining stock that is hyped based on bullish projections for a new tenement. Later, when it becomes clear the prospect is not what its promoters claimed, some investors will still hold on, based on the erroneous view that they can make their money back.

The motivations behind the sunk cost fallacy are understandable. We want our investments to do well and we don’t want to believe our efforts have been in vain. But there are ways of dealing with this challenge. Here are seven simple rules:

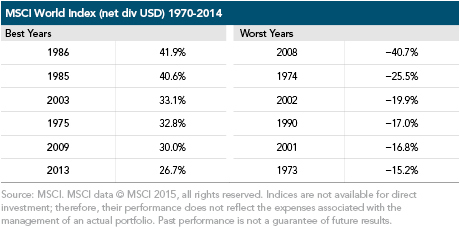

Accept that not every investment will be a winner. Stocks rise and fall based on news and on the markets’ collective view of their prospects. That there is risk around outcomes is why there is the prospect of a return.

While risk and return are related, not every risk is worth taking. Taking big bets on individual stocks or industries leaves you open to idiosyncratic influences like changing technology.

Diversification can help wash away these individual influences. Over time, we know there is a capital market rate of return. But it is not divided equally among stocks or uniformly across time. So spread your risk.

Understand how markets work. If you hear on the news about the great prospects for a particular company or sector, the chances are the market already knows that and has priced the security accordingly.

Look to the future, not to the past. The financial news is interesting, but it is about what has already happened and there is nothing much you can do about that. Investment is about what happens next.

Don’t fall in love with your investments. People often go wrong by sinking emotional capital into a losing stock that they just can’t let go. It’s easier to maintain discipline if you maintain a little distance from your portfolio.

Rebalance regularly. This is another way of staying disciplined. If the equity part of your portfolio has risen in value, you might sell down the winners and put the money into bonds to maintain your desired allocation.

These are simple rules. But they are all practical ways of taking your ego out of the investment process and avoiding the sunk cost fallacy.

There is no single perfect portfolio, by the way. There are in fact an infinite number of possibilities, but based on the needs and risk profile of each individual, not on “hot tips” or the views of high-profile financial commentators.

This approach may not be as interesting. But by keeping an emotional distance between yourself and your portfolio, you can avoid some unhealthy attachments.

Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. There is no guarantee investing strategies will be successful.

Dimensional Fund Advisors LP ("Dimensional") is an investment advisor registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to shifting market conditions. This content is provided for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services.